Wet-Socked and World-Weary

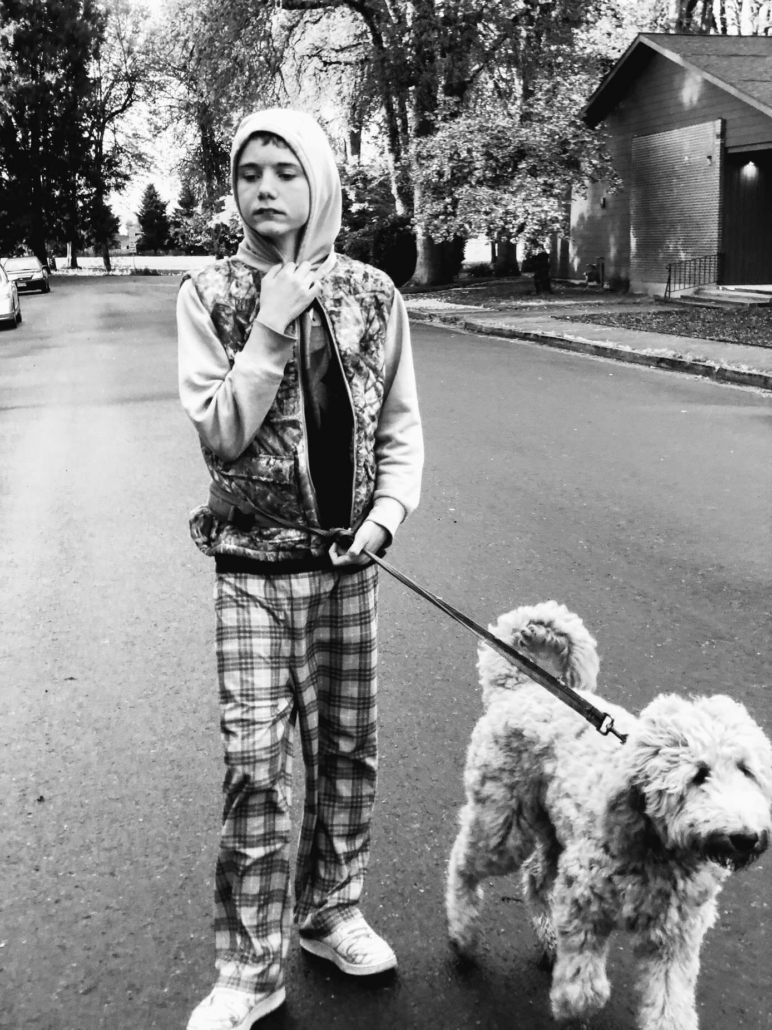

It’s a drizzly morning, and Jack is taking a walk with me. He had a rough night, which means Sara and I had a rough night, and now we’re trying to shake it off by meandering the streets of our wet little town before it wakes. A pair of exercising moms offer us a good morning, and I wonder if they can tell my boy is different. There is much about him that sticks out. Some of his uniqueness he owes to the autism spectrum. But some of the other stuff—the melancholy aimlessness on this morning walk, or the way he squints up at the rain—he gets from me.

It’s been two months since the world shut down, and we’re both tired. Jack’s tired of Zoom therapies and pixelated faces, and I’m about done with the games the world is playing—the tug-o-war over numbers and and courses of action. I’m tired of accusations and return accusations; of conspiracies and counter-conspiracies; of punches thrown and prophecies proclaimed and the near total absence of humility. If the world had broken in an off year, there might have been more good-faith arguments about how best to proceed. But since it’s an election year, every course of action is said to be suspect.

All of it is soaking my shoes, so I walk slowly.

How are we supposed to proceed? To shelter or to open? To comply or to defy? To mask up or to go plain faced and unafraid? The defiant ones don’t want to admit it, but they’re just as scared as the rest of us. Everyone is hyperventilating. We are afraid of COVID or of collapse. Choose ye this day whom ye will fear: the bodybags or the breadlines.

And I don’t claim to be above it. I think both threats are real. But you know what I’m most afraid of? Not of the coronavirus or of a great depression or that we are so plainly being ripped apart by mutual suspicion and resentment. No, my biggest fear is that we don’t care we’re being ripped apart. I fear that we’re okay with it. That we’re ready to rush in and pick up our side of the rope; to drag our neighbors into muddy agendas we barely understand.

The beloved disciple said that perfect love casts out fear. I don’t doubt him, but I want to ask him, “When? How long does it take for perfect love to work its magic?” Because it’s been two months, and we’re barely shuffling along, wet-socked and world weary, accumulating new resentments by the hour. Perhaps we need more time. Or a better sort of love.

We pass the boy’s old elementary school, and I can see he’s sad. I’m sad, too. I tell God so. I squint up at the rain and wonder whether people know it when they see me? Can they sense my heaviness? Can they tell something isn’t quite right?

Jack crosses the street with me, then changes his mind. He stops on the sidewalk–frozen in indecision, until I offer him my elbow. Then, he does something he’s done ten thousand times before: he slides his fingers around my arm. He doesn’t speak; the gesture does it for him. It says he knows he needs me. It says he will continue to walk with me, even in the rain. It says, rather imperfectly, that he trusts me. That he loves me.

We shuffle forward together, Jack and I. He follows my lead, putting one foot in front of the next until we reach home, a little less afraid.