Wild Wings and the Gift of Presence

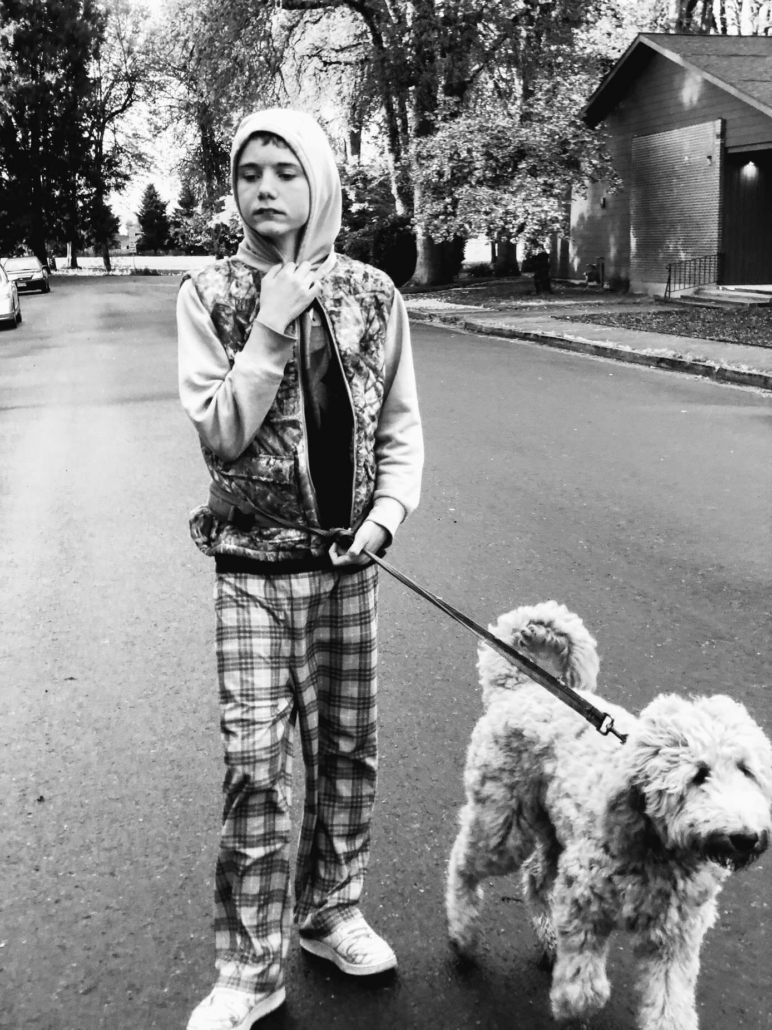

It’s the end of Autism Awareness month, and I want to tell you something I’ve learned recently from my son Jack, who was diagnosed at age 3 and is now 17. Jack has signisficant trouble communicating. Functionally, he is considered to be “non-verbal.” He speaks very little to us, and not at all to anyone else. And while he can read and type on his device, he hardly ever does so. His thoughts and feelings, dreams and pains, remain mostly out of reach.

This was excruciating in the early days, and I’ll be honest, it’s still hard for me sometimes. Maybe that’s because I love words. I love what you can do with them, how you can shape them to build stories, to leave impressions, to make people cry. A teacher once told me that language was God’s greatest gift to us since it is the very foundation of relationships. Without language, how can you really know a person? That idea stuck with me. I used to pray, “God, give Jack some form of language. I just want to know my son!”

Two weeks ago, my perspective shifted. Jack and I found ourselves in town together on a Friday afternoon with ninety minutes to kill. Normally, we’d have gone to see a movie, but there wasn’t enough time. I asked him if he wanted to go on a walk by the river. He mumbled something non-committal. It sounded like a yes, but it didn’t look like a yes.

Then, I realized we were only a half mile away from Buffalo Wild Wings. If I was with a friend, I thought, that is where we would go. We would order a beer and a basket of wings, and we’d watch sports on one of the many massive TV screens. I can’t explain why, but this felt like something I had to do with my son right then. It felt important. I had a rush of urgency that said, “Jack is getting older. This is no time for MacDonalds. We have to go to B-Dubs!”

The restaurant was mostly empty since there were no live games at that time of day. We sat down at a quiet table and the waitress came. Jack didn’t tell me what he wanted to eat or drink, but he didn’t need to. I’m his dad. I know won’t eat chicken wings, and probably wouldn’t fancy a beer, but boy does he love him some french fries and Sierra Mist. So that’s what I ordered.

I wanted to make our time special. I wanted to tell him how happy I was to be there with him; how I was proud of the young man he was becoming. But I didn’t, because I knew words would only frustrate him and probably spoil the moment.

So, for the next hour, we sat together wordlessly, sharing two baskets of fries. Jack blasted Disney music into big blue headphones and flapped two lanyards in front of his laminated picture—the one he carries in a protective folder. I sat with my IPA and my four versions of Sports Center. The sound wasn’t on, but I was okay with that. I was okay with the silence.

That’s not something I could have said before, but it’s true now. I am okay with the silence. Not all the time, but most of the time.

When I realized that simple fact, I remembered what my old teacher had said about the foundation of relationships, and I decided he was wrong. Language is one of God’s greatest gifts, to be sure. But there’s something else that comes first: Presence. Presence comes before language. Presence is the real foundation of relationships.

And this is what I want you to know if you have a loved one who struggles to communicate like my son does: your presence is invaluable. You must never consider it a small thing or underestimate its potency. Yes, I know words are important. I know communication is essential for a person to thrive in this cold, uncaring world. I’m not suggesting you stop working toward those goals. We haven’t stopped, and we won’t stop. But if progress is slow like ours is—even if words never come in the end—your greatest gift is this: you’re still there. You continue to show up. You figure out the songs they love. You order the fries. And you sit and share a long, extended moment. You share it all together.

Remember the laminated picture Jack carries? Well, it’s a picture of a television screen. An early 2000s Sharp Aquos TV. He used to watch all his movies on one of those. We have a Sony now, but the boy remembers that old model with real fondness. He carries the picture with him everywhere he goes. I don’t understand it, but the picture is important to him, so we respect it. Anyway, while he was staring at his Sharp Aquos that day, it occurred to me that we were surrounded by dozens of TV screens.

“Jack, check it out,” I said, gently tugging on his headphones and motioning to one of the monitors. “That’s not a Sharp TV, but an LG. And there’s another one. See that? LG. And another one. LG.”

A half smile crept up on the left side of his face as we studied the rest of the screens around the restaurant, comparing them with his picture. In his smile, I could see the truth: this son of mine understands us. This day. This rite of passage. He gets this connection we’ve built—this way of being without saying. There’s so much saying nowadays. So many words. Yes, I love words, but there’s real beauty in shutting them down sometimes. When we embrace silence, we don’t just give a gift to those who struggle to speak, we receive a gift too: the gift of THEIR presence.

I am thankful for my son’s generosity that day. And I look forward to spending another quiet afternoon with him at our new favorite hangout.