“When I was Young I Knew Everything”

It was twenty years ago. A lifetime. We were walking the streets of Manhattan late in the evening after a Broadway Show. There were ten of us — seven graduating seniors from a tiny Christian school in east Texas, and three adults. The big city awed us southern kids in all the ways you’d expect: the bright lights, the endless mass of humanity, and the breakneck pace at which they all went about their lives. It’s true they looked like ants from the top of the Empire State Building, and that was only appropriate. They never, ever stopped moving.

But even the spell of the New York couldn’t shake me from the fact that I was right and my friend was wrong, and I had to keep telling her. We had just seen Miss Saigon on stage, the famous story of a Vietnamese orphan girl and her American G.I. lover. Their romance produced a child, but the soldier had already gone home, leaving her to provide for her son as a dancer and prostitute (I might have some of the details wrong here. It’s been twenty years…).

“She was desperate,” my friend said. “What do you expect a mother to do?”

“It doesn’t matter. That lifestyle is wrong,” I told her.

She was done discussing it, but I wasn’t, so I kept pushing. Kept hounding her.

I don’t remember what I said, but I remember it was too much. My friend knew this side of me well. I was a brash eighteen year old who had to have the last word. She usually rolled her eyes and let me have it. That night, though, I’m pretty sure I made her cry.

When I think of that year, I think of the hit song that dominated our mix tapes: “The Freshman” by The Verve Pipe. The sad, grungy ballad opened with the words, “When I was young, I knew everything.” How fitting that I never understood the line back then.

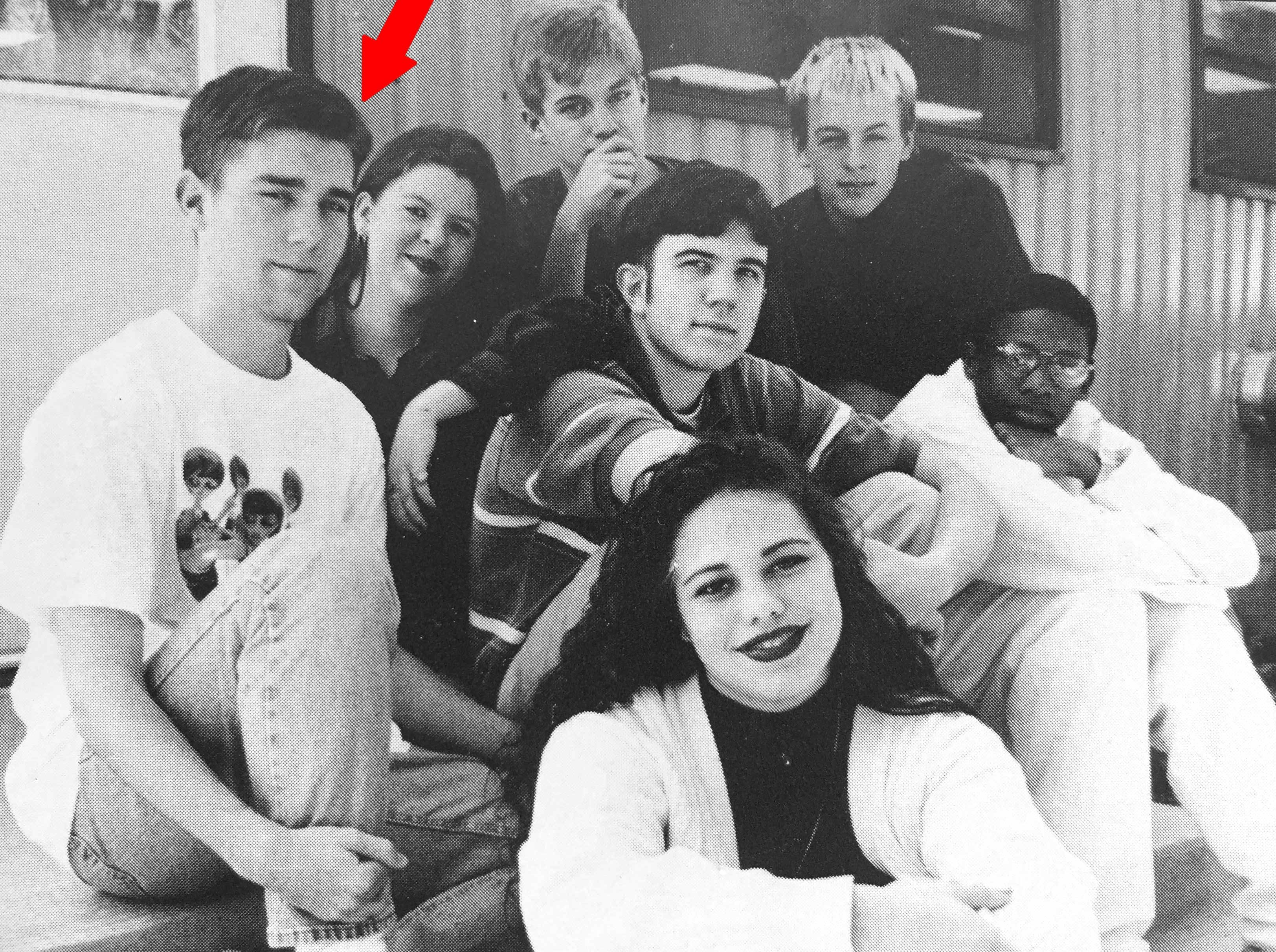

I wince when I think of those days. I wince because of the essay I wrote and read aloud in English class: how to always be right about everything. I wince because of the stupid thing I said in my speech on graduation night: “I can’t wait to throw my two cents into the arena of ideas.” I didn’t have two cents of my own to throw. I had pennies borrowed from other sources–some of them wise, but most just loud. I wince because even though I had never experienced a lick of genuine hardship, I walked with an arrogant strut, blasting my beliefs without a shred of gentleness or humility.

And of course, nothing has gone according to plan since then. It never does. Rather than changing the world with my big ideas, the world broke me.

***

“For the life of me, I cannot remember what made us think that we were wise…”

It is a cliche to say that men are fixers, and that cliche doesn’t fit me anyway. I don’t fix things; I have friends who fix things I break. But even for the inept guys like me, the stereotype usually fits. We crave resolution. We lean into it. When we don’t get it, we fall off our axis. Our worlds start to tilt.

My world tilted eleven years after I graduated from high school. Within fifteen months, I lost a dear friend to cancer, my infant son underwent open-heart surgery, and my three year old drifted into the fog of severe autism. For me, this triple-blow was especially debilitating, because up until then, I had never experienced one real crisis let alone three.

Answers had always come easily before that storm. Theology and logic had been obvious things. Truth glimmered so brightly, I wondered why everyone couldn’t just see it. Not after that.

Jack’s autism was the hardest because it lingered. It still lingers. And even though I’m not walking in perpetual numbness and sorrow anymore, his wordlessness, his seizing, his panic attacks and overwhelming shrieking… those things still throb beneath my surface. I can’t bring resolution to those pains in him or in me.

And yet those same pains do some good. They make me more aware of my need for God and for renewed redemption. They remind me daily that I am inept at life, and that I don’t have all the answers. Not anymore.

***

“And now I’m guilt stricken…”

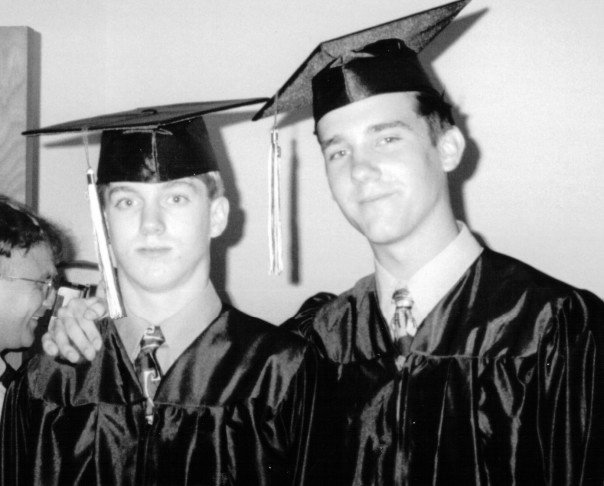

It’s been twenty years since I hounded my friend about the themes of goodness and morality; twenty years since I donned the cap and gown and charged into a world I couldn’t possibly understand. I don’t know half as much as I did then, and yet here I am, dealing out words and assertions for a living. It’s a little terrifying. I’m a teacher and preacher, and my writing is starting to reach larger audiences. I’m thirty-eight years old, which is safer than eighteen, I suppose, but I still look back at pieces I wrote just a few years ago and I wince again. Was I too flippant? Were my words haughty? Or maybe I went too far the other way, pulling punches beneath the ghost of an eighteen year old ignoramus. Will I ever be wise and gentle enough to say anything without regret?

It’s been twenty years since I knew everything, and I want to take it all back. I want to tell my old schoolmates I’m sorry for my arrogance; for my snotty, brutish arguments that carried neither substance nor kindness; for my hasty opinions and unfeeling judgments, and for the way I looked down on those who were limping. Forgive me. I hadn’t been broken yet. I wish I had been broken earlier. I can only pray I am broken enough now.

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out:

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out: