Story Advocacy: The Genius of “Life, Animated”

I have this old pixelated video of twelve month old Jack learning to walk. He is stumbling back and forth between me and his two sisters like a tipsy teddy bear, his mouth wide with triumph, and his eyes alive with laughter. They are so clear and cloudless. Sara is behind the camera offering whoops of victory, and we are all four cheering. It is the only real evidence I have that my memory didn’t play a trick on me. There really was a time before Jack went into the fog.

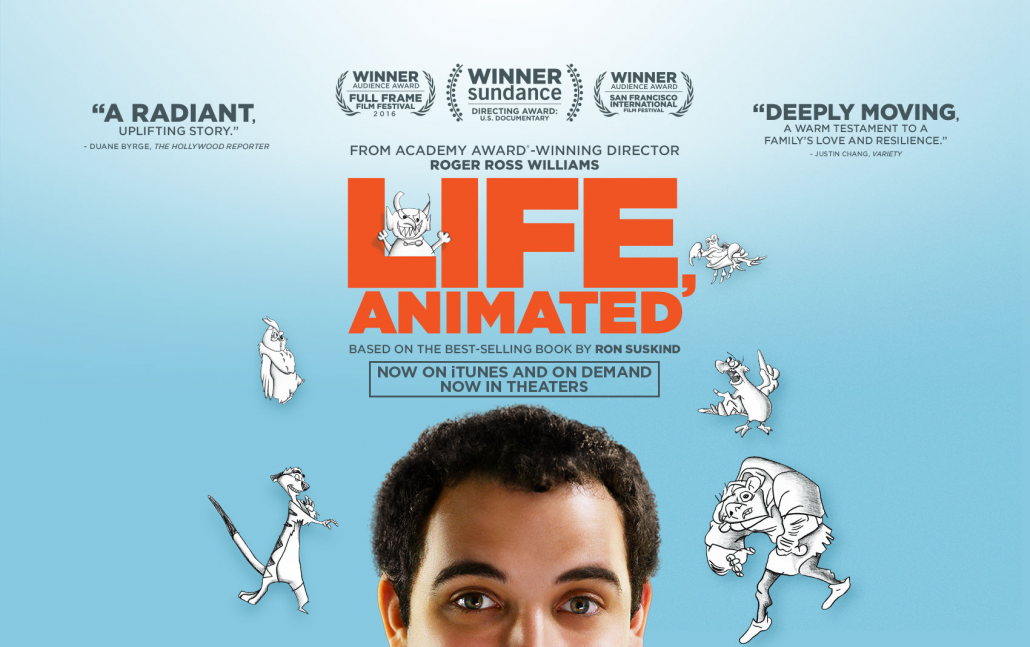

That clip represents the first bit of kinship I felt with Ron Suskind, autism father and author of the magnificent bestselling memoir “Life, Animated.” I fell in love with the book last summer, and was thrilled to learn about the film adaptation of the same name. Roger Ross Williams’ documentary is a masterwork of storytelling. It rocked me like few films have, and I think everyone should see it, especially those with loved ones on the autism spectrum.

“Life, Animated” is the story of Ron’s son Owen, who experienced his own regression into autism at the age of three. Like our story, this one really begins with a video: Owen is a tiny Peter Pan, and his dad is Captain Hook, and the two talk and whirl around in the autumn foliage, tumbling through leaves and laughter. It is a perfect picture with nothing missing.

And then… and then…

Regressive autism, Ron says, felt like a kidnapper.

The disappearance of Owen’s language and relational faculties felt like more a crime scene than a medical mystery. Ron’s recounting of those early days of wordlessness and distance would have cut my heart to ribbons even if his story hadn’t mirrored my own so well.

From there, the film shifts back and forth between Owen the child and Owen the young adult. We can see right away that he is no longer non-verbal. On the contrary, he is a grown man with grown language dealing with coming of age dilemmas that all grown-ups face. He has graduated. He is moving out on his own (sort of.) He has a girlfriend, and is looking for a job. He still has more than his share of challenges, of course, but he is facing his fears and beating them back. He even creates his own illustrated stories of Disney sidekicks. Owen is, in every way, growing up.

So how did he get there? That is what makes his story unique. Owen overcame his regression through the things he loved most: Disney movies. His affinity with the hand-drawn classics taught him not only how to speak English but how to interpret the language of human interaction. It didn’t happen overnight. In fact, it took years for his parents to get any language out of him, and much longer to get any actual conversation, but it happened. And even today as a young man, Owen relates everything to Disney. He quotes long strings of dialogue, sings the songs in convincing voices, and when he gets anxious, he paces in circles, mumbling his way through entire scenes. Early on, his family became students of all things Disney until they too could speak the language fluently. They entered into their son’s animated world, took him by the hand, and led him back into theirs.

Even before the book came out, Ron began preaching the gospel of “affinity therapy” for autistic children, and more and more kids are finding significant breakthroughs by way of their own passions. Our boy is finding success here, too. I wrote about it earlier this year. Jack’s internal index of Disney and Pixar movie quotes has given him verbal options to communicate with since he can’t come up with the words on his own. He pulled out a good one recently when was bundled up in his hospital bed for his sleep study. When the nurse raised the guard to keep him from falling out, he mimicked Winnie the Pooh trying to get out of Rabbit’s hole: “Oh help and bother. I’m stuck.” We shouldn’t have laughed, maybe, but we did.

The Disney connection isn’t what made me love the movie, however. It was the positioning. At age ten, my Jack stands between young, nonverbal Owen and Owen the young, emerging man. The gut wrenching days of no eye contact and no connection–those are over, thanks be to God. The heaviest fog has lifted.

But then there’s the future. This world is not built for boys like Owen and Jack–mysterious innocents as they are-—and that brings a fog of its own. I don’t like it. I want to fan it all away for him. I want to prepare the schools, the jobs, the friends for him ahead of time. I want the culture to make room for him, but I can’t do it fast enough. Time is working against us. The boy is growing too quickly, and we won’t always be here for him.

So what is a father to do? What is a writer to do?

Should he sound the autism awareness misery alarm? Should he sing a dirge across cyberspace about the rise in numbers and lack of funding? Or should he go the other way, carefully editing happy songs about spectrum living in order to promote autism acceptance? Ron Suskind answers the question by simply telling us Owen’s story.

Indeed, this is why I loved the film so much, and it’s why I want everyone to see it. We need more of this kind of advocacy. I want to respond to the endless tug-o-wars with a sound mind and a full heart. I want to meet them all in the middle and say, “Here is my son. He has immense challenges behind him and before him, but he is as kind as a Pooh Bear and as happy as a Tigger. His name is Jack. I hope you’ll make room for him.”

Life Animated is available online through iTunes, Amazon, and everywhere else.