On Praying Dangerous Prayers

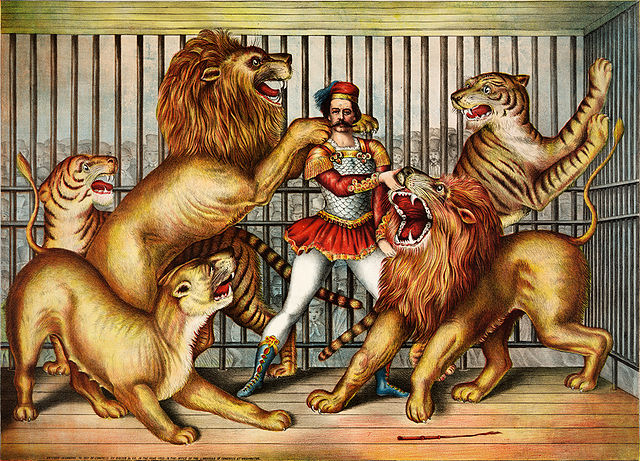

Once, there were three brothers who found a magic lamp. They were good brothers, passionate brothers, with a deep affection for justice. So when the Genie emerged and offered them three wishes, none of them even considered themselves. They all thought of the terrifying lions which had long threatened the safety of their village.

The older brother knew what he wanted right away. “We need awareness. I wish for an advanced early warning alarm system that will sound when predators are near.”

“Brilliant!” the second one agreed, “And lions are beautiful, but dangerous. So for my wish, I want for everyone in our village to understand just how dangerous lions can be.”

The Genie snapped his fingers. “Both requests… done.”

The two slapped each other on the back and turned to their younger brother. His mouth was twisted in consideration.

“What’s it gonna be, kid?” the Genie asked.

“Make me a lion tamer.”

* * * * *

I spent last week with a gang of young lion tamers in Texas who are not satiated by “awareness” alone. They stand out amidst a culture obsessed with educating one another. We pin colored ribbons to our jackets, and pat ourselves on the back for telling people why. We find enlightening quotes over filtered images. Then we pin them, share them, and urge our friends in 140 characters or less, “Be aware of my cause!”

We bloggers are often the most guilty, especially on sites like this one. We write about subjects that many people know only a little bit about. We say a few honest words about these subjects, and then, out of nowhere, people gush about how “courageous” we are for saying them. Because that word, especially, has lost its meaning. Its worth.

Real courage does more than speak. It does more than raise awareness about personal difficulties or societal sins.

Real courage does.

These young people I mentioned, they are doers. Even now, they are preparing to roll back blatant injustices in far off lands. Places the rest of us might not even be aware of. Places where injustice does not even bother hiding. They will smell it everywhere they go. It will break their hearts in a hundred places. And yet, they go with healing in their hands and songs on their lips.

They do not have to go. In fact, they are paying through the nose for the opportunity. But they are volunteering anyway, because they understand “what is good and what the Lord requires,… to do justly, and to love mercy.” They go because they ache for the broken. They go because Jesus went.

One of the evenings I was them, I told this group all about my son Jack, and about the risks that special needs children face. After my talk, one young lady opened her mouth to pray, and courage—real courage—came out. “Lord, give us opportunities to love these children. Bring them into our lives.” In another setting, with different people, those might have been empty words. Not in this group. I knew she meant them, because she already is doing. And I fully expect her request to be answered. Dangerous prayers usually are.

I want to pray dangerous prayers, too. I want to live a wilder story. After all, as Mr. Lewis reminded us, Christ Himself is not a Tame Lion.